Our founder & CEO Sebastian Sauerborn reflects on how his own upbringing and family history have shaped his views on a more sustainable food system.

He explains why it ultimately needs both city people and farmers to build a better food system, and how this understanding has led to founding Ashfount Investments.

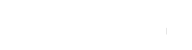

It’s a cool summer day in Edinburgh. As I am sitting here in my study and writing this, watching over the Firth of Forth in the distance, and the famous Forth Road Bridge under a grey sky, I think about my father. He passed away suddenly and unexpectedly around this time in July 2012. He was only 59 years old and he is missed by many, especially his eight sons and daughters.

In our family, there are several birthdays (including my own) and wedding anniversaries in July. Thus, as a family, this is a time of birthday parties, FaceTime calls and sharing memories on social media. Lots of opportunities for talking about our father, telling anecdotes, and reminiscing about the past. As you may expect, our father’s remembrance is important to us. And we are keen to keep his memory and legacy alive.

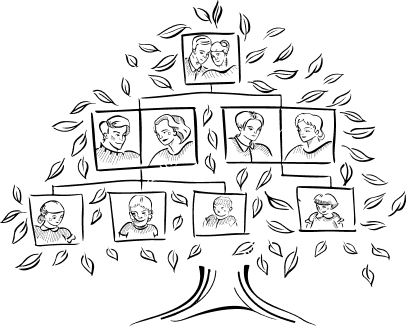

And as his children, we look into the present and search for anchors that connect us to our father, and our ancestors in general. Have we inherited certain character traits, gestures, strengths and weaknesses? As we are proud of our family we want to be worthy torchbearers and want to carry forward into our life time what our parents and grandparents began.

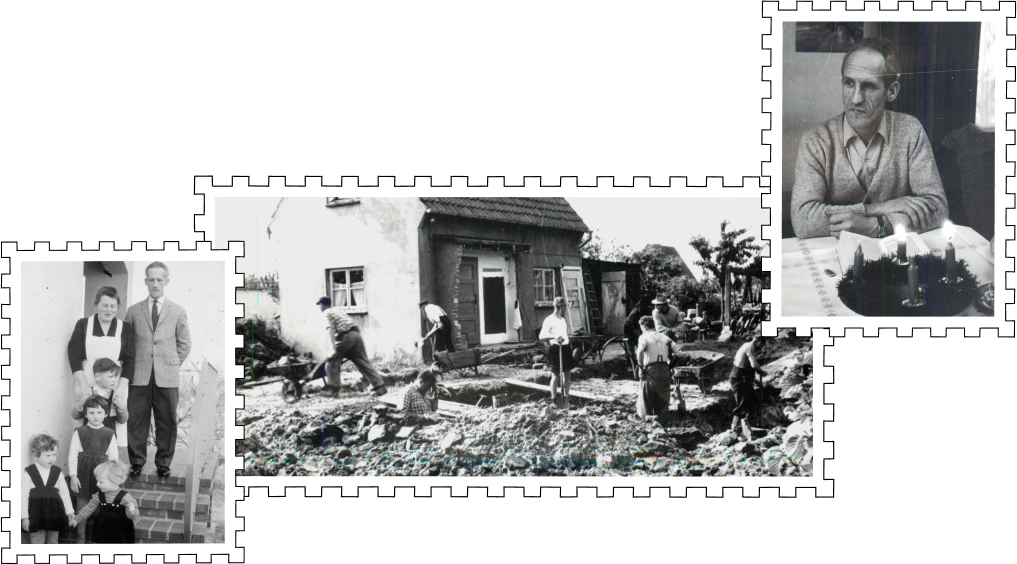

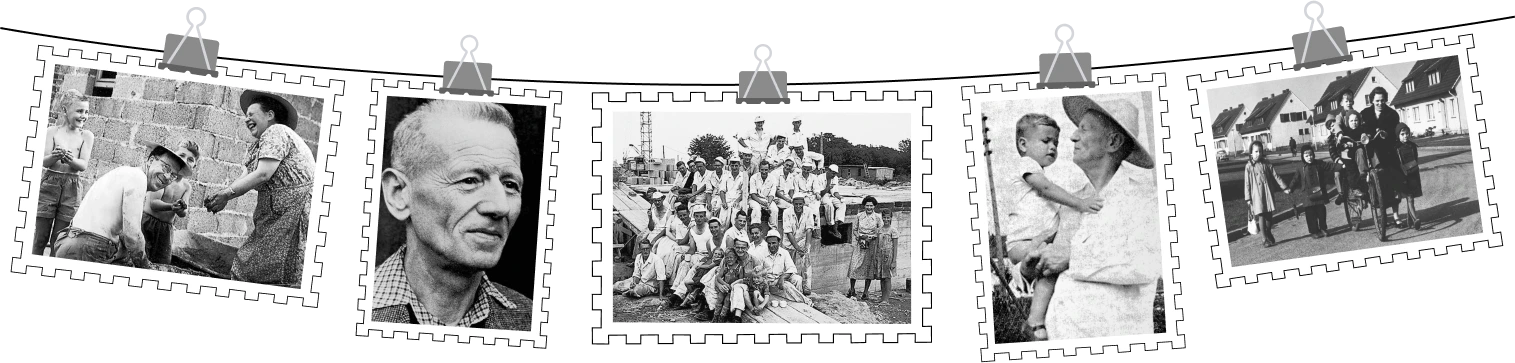

My father Martin as I remember him: in 1986, with me in 1983 and in 1995 (clockwise). All taken in and around Freiburg, Germany.

So as I am working to launch Ashfount Investments, my regenerative agriculture investment firm, my father, my grandparents and our family origins are constantly on my mind. And the more I think about it, the more I can see my father’s and grandfather’s handwriting all over this project. Indeed, as I look back, and as I read through our firm’s core beliefs, it is as I can hear them talking.

This venture feels almost like a calling, like continuing a mission or a family tradition, a legacy.

So I decided to write it all down.

I did a lot of digging in the family archives for this. I spoke to older relatives, acutely aware that there is an urgency to listen to their stories and record them, in order to preserve them for my own children and grandchildren.

So what you will read on the following pages is about the vision of Ashfount Investments and how it was shaped. When I connect the dots, I understand that what got me into farming and sustainable agriculture is rooted in my childhood and youth in Germany. And what I picked up about food and food culture from my parents and grandparents, and indeed the wider community that we lived in.

But before I do this, let me quickly recapture what Ashfount Investments is all about.

What is Ashfount Investments all about?

Ashfount Investments builds regenerative farming and food businesses in the US.

The aim of this is to contribute to a fair, sustainable and local food system that heals our land and soil and benefits everyone involved:

Farmers

Food Producers

Consumers

Workers

Grocers

At the core of this is the belief that the care for the common good, the community and creation is a good business choice and makes business sense.

At Ashfount, we believe that the best food system is a connected one. And by this I mean a living body where all members of the community participate in: Farmers, grocery stores, restaurants, consumers.

It is a system where all participants are at least partly familiar with the entire food production chain and each other’s responsibilities in it. It’s a system where everybody is on some level involved in food production. And where an exchange is not just an anonymous transaction but involves knowing each other on a personal level.

We believe that being involved in the food system is the key to making more responsible food choices that contribute to better health and a better society. Even if that involvement simply means to make conscious food choices, buy food responsibly, and cook family dinners at home (rather than consuming industrially made junk food).

You don’t need to be an expert to see this and you don’t have to be a farmer either. I am neither. Despite being the founder of Ashfount Investments and having owned ranches in the past, I can’t claim much farming heritage and pedigree for myself.

First, let me confess: My folks are not a farming family.

As far as I can look back, pretty much all members of my extended family have been urban dwellers with typical urban jobs and careers. We are a family of skilled labourers, like steel workers, electricians and carpenters. And we are also civil servants, nurses, engineers, middle managers, computer programmers. There have been and still are a good number of intellectuals in my family such as teachers, university lecturers, professors, writers, artists, opera singers. And a few entrepreneurs thrown in for good measure.

But no farmers.

Pictures of the land in Chile, close to La Serena, where Johannes and Ludwig farmed. Taken around 1992.

Or almost none:

As young men, my granduncles Johannes and Ludwig moved to Chile in 1953 to leave a still devastated Germany for a promise of free land by the Chilean government to German immigrants. They started farming with no prior experience whatsoever and the conditions were tough: This wasn’t the land of milk and honey. The 100 acres or so they each had been given by the government was in the Southern tip of the Atacama desert at the Pacific coast. Because of issues over water rights, Johannes couldn’t properly develop his farm and he returned to Germany after 8 years to become a teacher. Ludwig had more luck and the better land. He stayed in Chile and built a prospering family farm and other businesses that are still run by his family today.

And that’s about it when it comes to my wider family’s experience with farming. It just doesn’t seem to run in our veins. So when I talk about farming, regenerative agriculture and local food systems, these are not ideas I have grown up with on the multi-generational family farm.

The Experience of a Connected Food Supply Chain

Yet that whole notion of pigeonholing us in farmers and city folks, them and us, in dividing society up in food producers and consumers is a way of thinking I was not accustomed to.

Where I grew up, we were immersed in a culture where everyone was participating in the food system in different ways, some more intense than others. But yet we all shared a sense of being members of one organism that has different parts, but parts that are all connected and in a constant exchange.

There was a sense of unity among farmers, restaurants, consumers, grocery stores that was based on a transparent, locally focused supply chain, where the food chain participants knew each other.

As an urban and suburban family, it was instilled in us that food and drink are not just nourishment, they are also important manifestations of our culture and important building blocks of community. Being involved in our food system and production was a sign of being educated and civilised. Having awareness of the seasons and the variety they bring was cherished and something to be looked forward to.

Please don’t get me wrong: My family was in no way exceptional or anything else than just a normal, average family in South Germany. What I am describing is not so much my particular family but the sentiments and experience of everyone in our community. That’s just how things were in Germany, back in the 80s and 90s (and to some extent are still today).

Looking back, what seems most extraordinary about it today is how unexceptional and normal it all seemed back then.

Why We Can’t Rely on Farmers Alone to Change the Food System

And I believe this is the culture and the thinking we need to bring back if we want a better, fairer and more healthy food system. We need to get everyone involved again. We need to make everyone a participant of that food system.

Most of us don’t have a farming background. But we cannot rely on farmers alone to re-establish a culture where people get back in touch with their food and get involved in their food system. It is something that mostly non-farming folks need to work on. It is a responsibility we all need to take on.

This is a question of education in schools and at home, and more importantly it is living by example and “just doing it”.

This is the place where Ashfount Investments was born.

We want to build businesses that promote the ideas of a local food system, based on regenerative principles that heal both the land and ourselves. We want to build businesses that “just do it”.

It is so important that this thinking becomes part of our everyday lives and decision making processes as it holds the keys to a happier life, and improved physical and mental health. This is why I have started Ashfount Investments and this is what I want to leave as a legacy to my children.

So with no further ado, let’s talk about the wonderful “food culture” legacy that I have been left with by my parents and grandparents.

From Post WW1 Poverty to the Suburbs

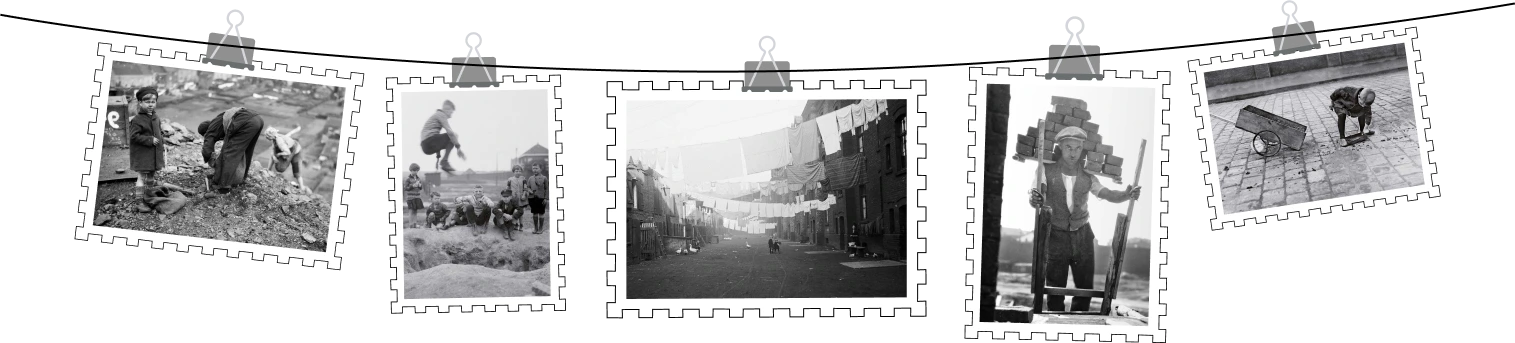

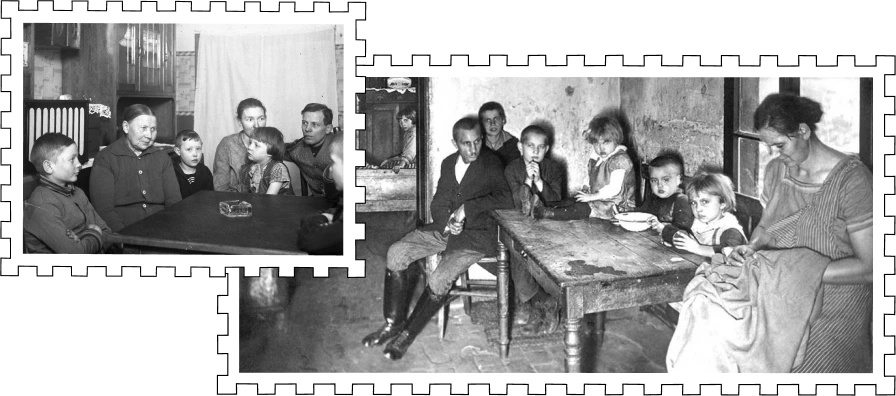

My late grandpa Gerhard Sauerborn grew up between the two world wars in Bremen, a major city in the North of Germany. They were a large Catholic working class family. Gerhard was the youngest of seven children. They were poor as many Germans were poor in those days, suffering from the economic aftermath and sanctions following WW1. A devastating misery that the German Kaiser had inflicted on the world.

Gerhard’s dad Lorenz worked hard, but as a steelworker there was only so much money he could make, even when doing 12 hour shifts. And that is when there was work. There was more than one prolonged period where Lorenz couldn’t find a job, one of many workers suffering during mass-unemployment.

And thus, although they were highly disciplined and frugal, money was always tight. So tight that little Gerhard never got a birthday present, except twice in his entire childhood.

In his memoir Gerhard writes:

“Sometimes our financial situation was so dire that we would only have potatoes and dill pickles for dinner, together with a dip made of oil and vinegar. Mother used to grow the pickles in the garden and pickled them herself in large clay jars. Especially during these difficult days, having the garden made a huge difference. Mother tended to the garden while Father was at work. We couldn’t afford the 10 cent tram ticket so Mother had to walk all the way to the allotment and back. During the summer months, when she came home from the garden at lunch time, her face was red and she was sweating profusely. So heavy were the carrier bags full of fruit and vegetables she was bringing home from the garden.”

I love that image of full bags of fresh fruit and veg, that humble abundance in the midst of bleak economic circumstances. I love how my great-grandparents never had their spirit broken.

Life Lessons & Quality Time with Dad in the Allotment

Lorenz was a man of little words. Often, when he came home after another back-breaking shift in the steel mill, he was too tired to even say a word. But when he spoke, it was significant. From an early age he instilled the idea in Gerhard to “make sure that you are not the anvil”, the one who gets brutalised and beaten up by others. By this, he was imploring Gerhard to take his education seriously and make the most of his abilities, gifts and opportunities.

And for Lorenz, one of many practical ways to raise yourself up, was to be able to grow your own food and thus depend less on others. So in periods of unemployment, he wasn’t idle but spent his days in the allotment tending to the garden and growing fruit and vegetables for the family.

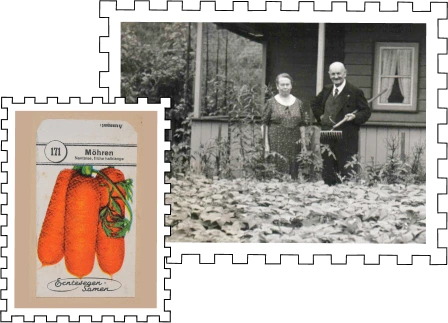

My great-grandparents visiting their former allotment in Bremen, Germany, taken after WW2. The other picture is an original carrot seed pack as sold in 1930s Germany.

Young Gerhard joined him wherever possible and sometimes they would be sleeping in the little garden shed overnight. It was like a little staycation amidst bleak times that Lorenz tried to make as positive for his youngest son as possible.

He worked as hard in the allotment, and maybe even harder than in the steel mill. And Gerhard, filling his stomach with what he picked in the garden throughout the day, did not only have quality time outside with his dad but also learned the important lesson that growing food can be a life changer.

Arriving in the Suburbs & Growing More Food

Later, after WW2, in the fifties, Gerhard had become an electrician and made a career with a local utility company. Having learned to save money as a child, what he earned was enough to build a simple but spacious 4 bedroom house for his family on a nice plot of land in the suburbs of Bremen. This was the house my dad Martin grew up in.

My grandparents Gerhard and Elisabeth when building their house in Bremen, and just after. Taken during the 1950s.

Behind the house they had a huge vegetable garden and orchard and they kept working it until Gerhard died in his late 90s. The garden wasn’t a hobby or a way to unwind. There was nothing romantic about it. What it produced formed the staple of Gerhard’s young family, another large Catholic family with five kids (my dad being the oldest).

Having learnt from his father, Gerhard knew that producing your own food can make your income go further. And he credited his ability to grow his own food with paying off the mortgage much faster than anticipated.

Make Income Go Further

In the basement of their house they had a pantry and they made sure it was always filled: Pickled and canned fruit and vegetables, jams, a huge potato storage in a dark corner and all sorts of dried and smoked meats.

Gerhard also kept rabbits for meat and chicken for eggs, as well as broilers – at least until it was made illegal by a local ordinance.

Grandma Elisabeth was a weaver by trade and she knew how to make the most wonderful tapestries and throws which she used to decorate their home.

Grandma Elisabeth working in her Garden. Bremen, Germany, 1950s.

When we visited them as children, it always struck me how lean and fit my grandpa was. He was never ill and stayed active until he passed away in that same house that he had built with his own hands, on the land he had worked year after year for over 50 years.

My grandparents weren’t farmers, although the size of their lot would certainly qualify for an urban farm today. They were essentially city people who had many mouths to feed and producing their own food seemed like the most normal thing in the world. Their situation wasn’t dire as their parents were. But they knew that by having a garden they would be able to save a lot of money.

Today, when we look back, it is that casualness, how obvious it was to produce your own food, that is most fascinating to me. Back in the day, there was nothing special about it. Most folks were involved in their food system in one way or the other.

A Vision of Thousands Urban Farms in 1950s Germany

That it should be normal for all families, even working class families, to be able to produce their own food is something that grandma Elisabeth’s father, my great-granddad Nikolaus Ehlen, campaigned for after WW2.

He was a local high school teacher in the Ruhrpott and an activist who stood up for the rights of working class families to own their own homes after WW2 in Germany. He set up a charity and started by lobbying the land-rich Catholic Church in order to secure cheap land on leaseholds.

My great-grandfather Nikolaus Ehlen with some of of the families he helped building homes. Velbert, Germany. 1950s & 1960s.

And then groups of ten men or so would work as a team to build each other’s houses. One was a roofer, one was a stonemason, one was a plumber, one was an electrician like Grandpa Gerhard and so on. By helping each other, they saved a ton of money as they only needed to buy materials. This was Nikolaus’s concept and it became extremely popular. The charity he established helped to build over 10,000 homes for working class families and does still operate today.

Why Each Suburban Family Home Should be a Regenerative Homestead

In his book “The Home that’s Suitable for the Family” from 1953, he laid out his vision on how a family home should be designed. Turns out he had thousands of urban homesteads in mind.

This is what he writes about the size of the food production facilities he envisaged for each home:

“The back garden of around half an acre will allow the family to keep an ewe which will provide 500 litres (110gal) of milk per year, 2.5kg (5.5lbs) wool for making clothes, 2 lambs and excellent fertiliser. By keeping sheep, using the dung and composting all food waste, even poor soil will become very fertile over time. Thus, we can acquire land with poor soil and improve it ourselves. The advantage is that land with eroded soil is much cheaper. […] The vegetable garden should have a size of around 3,000 square feet and should be separated from the orchard. Each family should grow their fruit trees towards the property line at the back and the sides of the property.”

110galof milk per year

5.5lbswool for making clothes

2lambs

excellent fertiliser

The Idea of Food Independence

Again – Nikolaus’s idea that every family home should be an urban, regenerative homestead was in no way revolutionary. It was widely practiced but with little thought or planning – it was just so common practise. Nikolaus’s vision was new because he proposed to design entire new suburban, working class developments where each unit would have their own food production capabilities. This would be making the families to some extent independent and economically more resilient.

That was regenerative agriculture in action. At its most basic, and smallest level and with plenty of common sense.

Nikolaus and the working class men and women he stood up for were not farmers. He lived in the middle of the Ruhrpott, the most densely populated area in Europe. He was a teacher. But he saw that every man and woman should have farming skills. He saw the benefits of being involved in your food system for each family, for society, for the land.

When My Dad Was a Bohemian Vegetable Gardener

This is where my own story starts to be interwoven into this rich fabric of a family history of growing your own food. And it brings us straight to the Black Forest in the Southwest of Germany.

The Black Forest is actually not just a forest but a mountain range that forms part of the foothills of the Alps. It gets its name from the numerous dark pine trees that grow in abundance. It’s around 160 km (100 miles) long, stretched along the right side of the Rhine Rift Valley. The highest elevation is the Feldberg with an altitude of around fifteen hundred meters (around 5,000 ft). It’s a sparsely populated area, dominated by small towns and villages.

Well known delicacies from the Black Forest include “Black Forest Ham” and “Kirschwasser” or “Kirsch” (a brandy made out of fermented cherries). Not to forget the ever famous and delectable “Black Forest Gateau” a chocolate cake with cherries and cream and topped with shavings.

I was born In the city of Freiburg im Breisgau, in the Rhine Rift Valley and right on the western edge of the Black Forest. It has a population of around 200,000.

Moving to the Country

When I was around 4 years old, my father, then in his late 20s, had just published his first (and only) novel with modest success. Yet he believed he had found his true vocation and decided to make it as a writer and also to study philosophy on a part time basis. And so my parents and us three children moved from the city into a tiny village with 500 inhabitants high up in the Black Forest, an area called “Hotzenwald”. We rented the old presbytery for around 60 Euros/Dollars a month. Very little money even back then.

It was a massive house with massive grounds. I was around five years old then and living the dream. The front of the house was facing the village church (it was a presbytery after all), but behind the house was just endless open space. Our own large garden and behind that pastures with some scattered old apple and pear trees. As it is the law in Germany, nothing is fenced off unless there is livestock grazing. Even back in the 80s most farmers used portable electric fencing.

Me and the old presbytery. Unteralpfen, Germany, early 1980s.

My parents were always skint. They relied on what my dad’s very occasional freelance writing gigs paid. My dad was too proud to ask for government handouts and looking for other ways to make ends meet.

And so, when he was on the phone to his parents one evening talking about his financial woes, granddad Gerhard recommended that they start a vegetable garden and grow their own food. It seemed obvious to Gerhard (who had no time for his son’s ambitions as a writer): We had plenty of land that we could use, good soil, and he believed my dad had plenty of time on his hands.

My dad agreed and with money borrowed from the family, he bought a two wheel tractor called “Agria” and started to work a vegetable field around the size of an acre.

The abundance in food that we soon started to experience was breathtaking. Of course we never had to go hungry before, but now the variety of food increased ten fold. Every day was a feast. Tomatoes, carrots, potatoes, spinach, cabbage, salad, strawberries…. I loved experiencing the seasons.

Homemade Elderberry Juice, Raw Milk & Raw Eggs

My mum started canning and pickling and I still remember those cosy winter nights by the wood stove having homemade bread with peanut butter and homemade jelly earlier in the year.

Her home pressed elderberry juice was one of my favorites, and it is one of the most commonly used medicinal plants in the world. It is still taken as a supplement to treat cold and flu symptoms.

Homemade elderberry juice and spread, just like mom used to make them.

Picking up milk fresh from the farm.

Every evening, I would go to a local farmer in our village. It was a 10-minute walk, and I carried a milk canister made of aluminum. I would buy fresh warm milk, straight from the udder of the cow. Of course, walking back home took much longer because the canister was filled to the brim with two liters of milk.

I would also buy newly laid eggs, which I carried in a protective basket in my other hand. I will always remember that the farmer’s wife sometimes gave me a treat, a raw egg, and she insisted that I punch a little hole in the top of the egg and that I eat it straight away. Nowadays, of course, eating a raw egg sounds disgusting.

Sometimes we would head down to the local fishery to catch fresh trout. This was not done using a traditional fishing rod. Instead, some food was thrown into the water, and the fish would immediately come to the surface. I was given a net to catch the trout. I would proudly take my catch home for my mother to prepare our evening meal.

Sadly, my dad grew tired of being a writer and a student after a few years. So we moved back to Freiburg and left the old presbytery behind. I remember these years as a wonderful time, full of simplicity, great food. And even though my parents tell me we were poor then, I never felt richer.

My dad was not a farmer. He was a poor, aspiring writer and philosophy student back then. But in the time of need he knew what it took to make growing food change his life for the better.

My parents Martin and Ricarda in front of their vegetable garden. Unteralpfen, Germany, early 1980s

Grandma, the First Conscious Consumer I Knew

Even though I still remember how much I hated being back in the city, there was one upside to this move: I got to spend a lot of time with my grandma. I had a special relationship with my Grandma, and we had a very close bond.

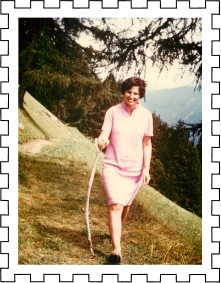

Grandma Ricarda hill walking, 1960s

After we had moved back to the city, she would take me on day hiking trips into my beloved Black Forest on the weekends. By car, it would usually be a fifty-minute drive from Freiburg. However, my Grandma preferred to take the scenic route and so we used to slowly climb up windy, narrow mountain roads in her little blue Japanese car. It seemed to take forever to arrive but I loved it.

I treasured our hikes, and along the way, we could view the farms with cows grazing in the fields. In the late afternoons, we could watch the farmers herding the cows back from the pastures into the barns as it was time to milk them. I missed living in the old presbytery in the village, but being around cows and in the fields with my grandma from time to time comforted me and made the transition to the city easier.

Grandma was my mom’s mom and had a significant influence on my life. Only in her 50s, she was quite a young grandma then, very active and full of energy and enthusiasm. She was a schoolteacher through and through and loved to teach and to pass on wisdom. A widow who had never remarried, she lived on her own in a modest terraced house that she had wonderfully decorated with antiques.

She was the only person in the 1980s I knew that was very health-consc when it came to deciding what to eat. She always favored organically grown food. She introduced me to whole wheat bread, health stores and a predominantly vegetarian diet.

But Grandma was different from my dad’s parents when it came to food. She wasn’t “hands on” at all. It would have never crossed her mind to grow food. Indeed, she hated cooking and preparing food. It wasn’t her thing and she wasn’t good at it. In fact her cooking had an infamous reputation in the family. I remember once she tried to make rice pudding for us kids by simply throwing whole grain basmati rice into boiling milk. Yikes.

Grandma Ricarda as I like to remember her. 1980s.

But nevertheless, she was very educated about nutrition and strived for a healthy diet. For starters, she didn’t eat a lot of meat. She would often have her lunch after school in a vegetarian restaurant – the only one of its kind in the area. Back then she was the only one I knew who frequented that place. When she took me there for the first, it felt like visiting a foreign country. Lots of guests with long hair and wearing sandals. I was curious but also a bit bewildered.

Grandma was as selective about her grocery store shopping as she was about the restaurants she frequented: She planned her shopping for food, and she would drive for miles to go to a particular shop if she wanted to buy those foods that she thought were good for her to eat. I enjoyed our food shopping excursions, although I never quite understood why she went through all the trouble, as she didn’t enjoy food or cooking. For Grandma, food was mainly about nutrition and getting the most nutritious food, even if she didn’t particularly like it.

That attitude paid off. She lived a long and healthy life, and when she recently passed away, she was almost a hundred years old. She never had cancer, diabetes, heart issues or any other major health conditions. As she was a great believer in homeopathy, she credited her numerous pills and tinctures for her good health in old age. I believe it had more to do with her lifestyle and food choices.

She was in many ways the first conscious food consumer I experienced in my life, long before it became commonplace. She was not a farmer, yet she was deeply involved in the food system by her conscious choices as a consumer. Even if she wasn’t a food connoisseur, she went through the trouble of making a great effort to source food well and eat well. And by that, she was making a statement and set an example as a food buyer.

Later on, in her 80s, Grandma Ricarda visited me in London. These pictures were taken during that visit in 2005. The main image is her with my son Kilian.

Teenage Years in the Bourgeoisie

By the time I was a teenager, my family lived a cosy, middle class urban lifestyle in Freiburg. My father had found success in business and thus we were, even as a large family with eight children, quite comfortable.

We had moved into a massive eight bedroom duplex in the posh Wiehre, a residential district in central Freiburg. This part of the city is dominated by spacious four to five floor apartment buildings constructed after the Franco-Prussin war in 1870/71. It’s the last war Germany won and it brought significant wealth to Freiburg, mainly from reparations.

We call this time in German history the Gründerzeit, or “Founder’s Time”, and the architecture expresses a mix of cultural refinement and national pride. Think high ceilings and parquet floors. Think the German version of Victorian middle class Britain, bourgeoisie through and through.

I remember these years as a very happy time. And, as you can imagine, food played a pivotal role.

My parents were a very sociable couple and they loved to host guests. Almost every day we had someone visiting us. Friends of my parents. Aunts, uncles, cousins. My father often brought colleagues home from work, and they brought their wives and families. The big kitchen with its massive Danish dining table made of thick wood was the gathering place.

As you can imagine, these weren’t very formal affairs. We were a family of 10 and whoever was visiting that day would join us for our family dinner. We had what felt like a very open house. Guests were always welcome, even at short or no notice.

And then, once the children had gone to bed, my dad served the good bottles of wine to his guests he had always stocked. Often visitors would stay until late at night and we children fell asleep to the distant, yet reassuring sound of the grown ups’ laughter in the kitchen.

Enjoying Food Together

Besides these casual get togethers, my mum often organised dinner parties and barbecues in the summer. Mum loved cooking and she didn’t mind preparing food for large groups. Similar to my dad, she enjoyed spoiling others with food and by sourcing high quality ingredients on the local markets to cook delicious dinners for the family and guests.

Yes, as a family we loved our food and drink and we loved to express ourselves through good food and drink. Indeed, serving someone a good meal and inviting them for dinner seemed the primary way for my parents to show appreciation to someone. They believed the way to anyone’s heart is through their stomach. For them, it had to be a visceral experience, something sensual and tangible. Deeds, not words. For them, living friendship and being family meant breaking bread together.

This also included frequenting the many local restaurants in Freiburg and surroundings areas often and with great enthusiasm. My father always insisted on picking up the bill. As you can imagine they were very popular as friends. They were the life of the party and everyone enjoyed their company because it was clean, wholesome fun.

I always thought my parents had a great marriage. There was an infectious energy radiating from them and others genuinely enjoyed their company. As it is often with great marriages, their example reaches deeply into their community of friends. They are a positive influence for many other couples and families. They symbolise hope and confidence and give strength to many who doubt, by just being them.

This was certainly true for my parents and I was proud to be a part of my family.

And thus, it doesn’t come as a big surprise that I never felt the need to rebel against my parents. I thought we had a great life and if anything, that was the life I wanted for myself. What was there to rebel against?

Indeed, I often preferred spending my evenings with my parents and family at home. I fondly remember the many warm summer evenings that we spent on our big roof terrace with its panoramic views over the old city, the cooling brise coming from the mountains at night. My parents, some work colleagues or interesting friends, their spouses and us older kids. Conversations were about business, politics, often America, faith and many other matters. I listened intently and sometimes contributed to the conversation. I was only 15 but I felt like an adult. I much preferred this then hanging with teenage friends, occupying ourselves with what seemed childish and immature activities.

Learning to Love Local Food and the Seasons

This little excursion into my teenage years may seem a little off-topic but it is not. This is because the community aspect, the sharing, is such an important element of a sustainable food system.

There are reasons why in the Bible many of the most important events involve eating: Manna in the desert, the wedding of Cana, the multiplication of bread, Jesus eating with sinners, the last supper, Emmaus and so on – they are all about eating, and they all involve eating together.

Eating together strikes to the core of what we as humans beings are: People of flesh and blood, and people born to be in community with each other. No man is an island.

And it is that community aspect of food – community beyond the core family – that I picked up from parents. It is potentially the most important lesson of them all, and the most important element of our work at Ashfount Investment: Bringing people together through food.

Food Through the Seasons

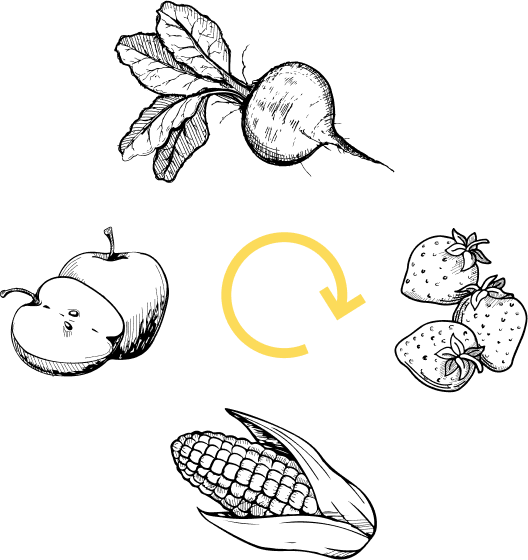

Closely linked to the community dimension are the seasons, and the seasonality of local food and local feasts and celebrations.

I grew up with these seasons; they were part of my everyday life. It wasn’t that fruits were shipped in from somewhere at the other end of the world. We saw the trees growing in the fields, watching and waiting, with expectations ready to sample each and every seasonal food offering.

When you follow those cycles, then you can compare what is growing and ripening with what the supermarket is selling at that time. Then you will know which are the local and seasonal fruit and vegetables. The seasons make you appreciate the fresh, just-picked produce in terms of making food special.

One of the unique things, in South Germany, is the wine region. The fall may be in late September, and the wine festivals would be a highly celebrated part of the seasonal, social and tourist calendar.

Each and every village had a small wine festival. Each weekend, we would go to another village to celebrate their wines. We would go with friends or with family, and we would have a good time. Wine for the adults and grape juice for the children. Kaiserstuhl wine is one of the best red wine produced in Germany, and it has won many awards.

Life flows with a natural rhythm that is determined by the seasons. The different fruits and vegetables change with the seasons. Foods become very special. The farmers are allowed by law to open their own seasonal restaurants and to create a menu from their own harvest. They set up a few party tables where people stop and enjoy a meal. It’s very basic. It’s very, very cheap. A minimal menu, maybe five or six seasonal special dishes were on offer.

Interestingly and specifically what I found so different from growing up in South Germany when compared with the States or the UK, is that they don’t seem to recognize the whole seasonality of things. I remember when I lived in Florida, they had crab season and deer season, and of course, Easter and Christmas, but other than these, there was not much emphasis on seasonality, especially in terms of seasonal food.

In Germany, there is more structure around seasonal foods and wine, with so much to look forward to and celebrate. In spring and autumn (April/May and September/October), beer festivals take place in Stuttgart. The Munich Oktoberfest is in the fall, and in late November and early December, the Christmas markets open for buying food and gifts for family and friends.

‘Spargelzeit’ (asparagus season) one of the most beloved traditions in Germany

A good example for seasonality is the asparagus season.

Two of the most famous asparagus-producing areas in Germany lie in Baden-Württemberg, namely Schwetzingen and Bruchsal. Schwetzingen, which lies south of Heidelberg, claims to be the “Asparagus Capital of the world.” Bruchsal, near Karlsruhe in Baden-Württemberg, boasts the largest asparagus market in Europe.

White asparagus (Spargel) is also known as white gold. Asparagus season is in the spring, and it starts from mid-April and ends mid or late June. Farmers sell asparagus by the roadside. Fresh asparagus is found in abundance at the food markets.

During this time, everywhere, everything is about asparagus! The restaurants have a special seasonal menu full of asparagus dishes, for example, asparagus with hollandaise sauce, cream of asparagus soup, asparagus salad, asparagus with ham, or bacon, or even with schnitzel.

To grow white asparagus takes three years of hard work before the first crop is ready for harvesting. In the first year, the farmers dig deep trenches in long rows, and the roots are planted. In the second year, the plants produce flowers. During the third and most crucial year, the farmers pack compost and sand to surround and cover the asparagus, and then in the spring, the asparagus is ready to be harvested very early in the morning.

The reason why white asparagus don’t turn green is because of the way that they grow underground and are protected in the deep trenches and covered. Asparagus only turn green when exposed to the light.

Of Cherries and Strawberries, And Game

Another example for seasonal food as I experienced it are the cherry and strawberry seasons.

During the strawberry season, you can go into the field and pick and eat as much as you like. As a child, I remember eating so many that I almost felt ill. At home, we would eat strawberries and cream and make delicious strawberry milkshakes. When you buy strawberries in season, they are so much better and sweeter.

Then there is still the cherry season to look forward to. Cherries being sold by the farmers along the road, or you can pick your own cherries. We had cherry trees in our backyard because they are easy to grow. Our homemade cherry jam was delicious with fresh bread on a cold winter’s day.

Then take the hunting season in the autumn.

Most local restaurants had a seasonal menu with several different game dishes. Mostly those restaurants wait to see what the hunters bring back to sell, and it would be cooked that very same day.

Ashfount Investments was Founded to Build Regenerative Farming and Food Businesses in America

I have shared these vignettes from my own upbringing and family history to explain what got me interested in our food system and farming. I am sure you will have similar stories in your own family. Most of us will just have to look back a generation or two to find examples of family members who were involved hands on in the food system and in food production. It used to be so common that we all share that collective memory.

It runs like a thread though our thinking, and there are probably deep evolutionary causes for this.

Small-scale farming and homesteading in America for a family’s own needs was common until quite recently.

Big industrial food companies take advantage of that when they decorate factory food with red barns and cows grazing on lush green pastures. They connect their junk food to what family farms look like in our collective memory. It really is manipulative.

But this is also good news because it demonstrates just how sacred and ingrained our unconscious awareness of a better food system really is in our mind. Even if we can’t necessarily explain it, we instinctively know what is right and we know that factory farming is evil.

And reconnecting to that natural conscience that we all have is the first step to make a change. Because really none of these are new ideas. This is as old as humanity itself.

The next step is to change our behaviour as consumers and make food choices that help make an alternative food system viable.

In my experience it’s often very basic logistical issues that prevent us from making better food choices: We shop at the grocery store and it’s too inconvenient to also go to the farmers market. When eating out we are not aware of restaurants that source locally and responsibly.

Our Mission is Simple: Let’s Do It

Ashfount Investment is not a think tank. I am an entrepreneur and a “doer”. I set up Ashfount Investments because I believe that regenerative agriculture is a way to farm that can help restore sustainable food systems similar to the ones I experienced in my childhood and youth.

And with Ashfount, we want to build businesses that just do that and put these ideas into practise. Not just farms, but also food companies that use ingredients produced by regenerative farms. And media companies that promote the idea of local, sustainable food systems.

Just doing is, just trying it out, is often better than wanting to do it perfect and wasting precious time.

Changing the food system and the world, one farm at a time.

We do this in the US because we believe that the US is much further down the destructive path of industrial farming and food production. There is more to do but there are also more opportunities.

The US is poised, prepared, and capable of being in the position to start this process that includes the roles of both city dwellers and farmers in building a better food system.

Changing the Hearts and Minds of Americans

COVID-19 has been an unexpected awakening on how a small virus can compromise a long and complicated food chain, how transport and closed ports can make relying on the global food chain risky in terms of both delivery and contamination.

I believe that it’s because we are no longer connected to a food system. That is why we became so vulnerable during the spread of the virus. It brings to our attention the need for the revival and restoration of a better food system.

The current food system is not suitable for our health, and it is not good for the environment. In this day and age, it’s shocking that obesity and malnutrition are widespread diseases—obesity from overeating and malnutrition from incorrect food choices.

The lack of a relationship with the food system is because the food is produced somewhere far away or in some factories. What we cook and the ingredients that we use bear little resemblance to food growing in fields. We have no idea where the food that we eat comes from.

What is the answer? What type of better food system do we need to put in place?

There is no quick fix. What is required is a shift in culture, which is a gradual process.

It starts by taking some small steps:

The first and foremost, step that is paramount for any progress to be made is that we redevelop a connection to food.

We can achieve that if we participate in the food system.

The easiest way for us to participate in the food system is to cook our own food. Everybody can do that with no exception.

We need to buy fresh and seasonal ingredients. Even if you don’t go to the farmer’s market, make sure that the ingredients are either organic or locally sourced by the supermarket. Most supermarkets provide that option.

Make food preparation a visual and aromatic experience. Chop the onions and listen to them sizzle in the olive oil.

Wait for the food to cook for an hour, stirring occasionally. Don’t rush; let the food simmer.

Look for old family recipes or find new ones on the internet.

Enjoy sitting at a table with the family, chatting and eating delicious and nutritious food.

Compare this to just ordering pizza or takeaway food or worse still buying some convenience meal and throwing it in the microwave, with family members eating while watching TV and posting on social media. It is so unhealthy.

Although this is a “Generational Project” as human beings, our brains are wired to habits. It is in our genes. By doing something repetitively, the brain starts to want to do this as an automatic choice. It becomes so entrenched in the brain that it becomes an excellent habit. Even if you are not totally convinced, about all these ideas about food, if you just start without overthinking it too much, the changes will automatically happen. Often by implementing simple steps, your life will start changing. It’s part of the human brain wiring. It’s part of the “Food Culture,” and your health ill automatically improve.

When I think of all the investments and agriculturally related ventures that I am involved in, they are associated with the land, and the community is at the heart of them.

Visualize families sitting down to a home-cooked meal. It’s about developing a healthy lifestyle and changing the food consumed to one that is sustainable, both for the land and for the people.

It may be a big step for people to start to consistently prepare their own food with fresh ingredients and with a conscious attitude instead of being in a rush. To stay away from the last-minute dash into a grocery store, grabbing something from the convenience food shelf without thinking much, rushing home, throwing the food into the microwave, eating it in haste. This is a recipe for a nutritional disaster.

Compare this to deciding to buy bread from a family-owned local bakery or meat from the family-owned local butchery. By supporting local food businesses, the money stays in the community, and it helps to keep the community together. It helps to create employment, and it’s a win-win for everyone.

Even if only five percent of the food is bought directly from the farmer’s market. Even with that minimal amount, it will keep increasing, and once it reaches a more critical point, it will be challenging to stop that change from happening. Learn more about farming.

The highly complex supply chains in the food industry are easy to break down. If something like the pandemic happens, there are too many steps involved, and the supply chain breaks down. A local food system has fewer steps involved and is more resilient.

I think that what we need to strive for is the sort of consumerism where local becomes almost like second nature.